Autism, Coronavirus, Anxiety, and Strategies to Cope with it All

Coping. My guess is that if you are reading this blog from Autism Society of Greater Wisconsin, you or a loved one needs coping strategies for this massive pandemic called the coronavirus. That goal is what this blog is for; to provide adults living with Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or loved ones of those with ASD, with tools to cope with anxiety surrounding the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

In most of the patients with ASD I have worked with, and in my own experience having ASD, anxiety is a huge struggle. In adults with ASD, it has been reported that somewhere between 31-51% have some form of an anxiety disorder (1). In my own experience with my anxiety, I can tell when it’s at play and when my mind is “jumpy”. I like to refer to it as “monkey brain”. I tend to think of a group of monkeys throwing my thoughts around. How disruptive is that? A group of monkeys throwing your thoughts around. I can feel it. My stomach gets in knots, my hands get clammy, and sometimes my heart races faster. It’s as if my body is reacting to the movement of the monkeys in my brain.

If you asked those closest to me how they know I’m anxious, they would tell you a couple of things. They would start by telling you that all I want to do is plan. For instance, when they want to talk to me about how great something is, and I’ll already be planning something six months down the road. Aside from the future focus, they might also mention that if plans change, I lose my cool — they encounter a hostile and loud version of Sean. Finally, they would tell you they know I’m anxious because I continue to repeat myself over and over, and need to just do this until I calm down.

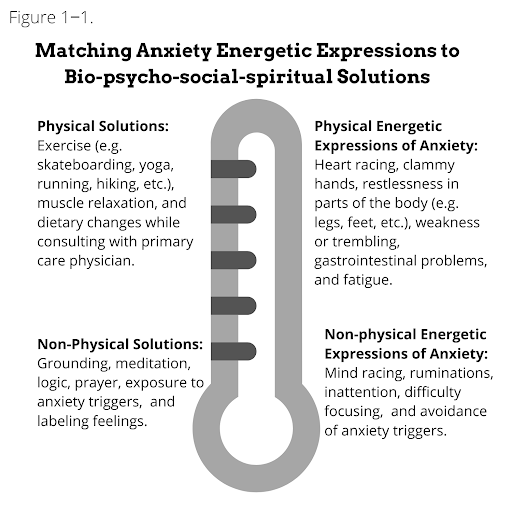

So how do we manage anxiety around this coronavirus? Both professionally and personally, I tend to think about anxiety in terms of energetic expression. That is, how is the anxiety presenting itself? Is it showing up as heart racing because I’m stuck on something that is changing (i.e. am I ruminating?), or is it showing up as tension in my clavicle? How anxiety shows up tends to be on a spectrum, and I try to match it to the Bio-psycho-social-spiritual solution to the form it takes (physical or non-physical, high or low intensity). See Figure 1-1.

So, what does the research and personal experience tell us about the effectiveness of some of these interventions on anxiety in ASD? For instance, when my significant other tells me she isn’t up to going out with friends, and we have been planning to go out with them all week, my anger level may go from a level to 2 to a level 7 pretty quickly. Upon putting down the phone, my forearm muscles may tense, my hands clasp, and I may not really want to talk with my significant other for a bit. As we know from working or living with people with ASD, rumination is common. Rumination is defined as, “A tendency to think repetitively about the causes, situational factors, and consequences of one’s own emotional experiences, and can be conceptualized as a form of nonacceptance of emotion.” (2). So if a person like myself, with ASD is ruminating about plans changing, energetically speaking, how is the anxiety presenting itself?

In this scenario, we know a couple things: First, my anger went from a 2–7 relatively quickly. Second, my arms are physically showing signs of an increase in tension in the body. Third, I am avoiding the anxiety trigger. Fourth and finally, I am replaying negative thoughts over and over in their head, reinforcing the anger at a level seven. So, if we refer to Figure 1‒1, what combination of solutions might work to address this presentation of anxiety in ourselves or the person we love? First off, we know that the anxiety is presenting itself in both a physical and non-physical expression, so solutions need to be both physical and non-physical.

Physically we might see solutions looking like:

Exercise

A well established intervention in patients with Anxiety and ASD is exercise. According to researchers, benefits of exercise include, “On-task behavior, academic responding, and appropriate motor behavior (e.g., playing catch) increased following physical exercise” (3). Meaning that exercise, whether it be in response to anxiety or ASD, results in increased executive functioning (the planning part of the brain). People with ASD might have specific physical solutions already identified, if a high interest includes physical activity. For instance, I have an interest in bouldering (a form of rock climbing that is performed on small rock formations or artificial rock walls without the use of ropes or harnesses). This interest, while in some ways isolating, doubles as a physical coping strategy that can increase my socialization. Bouldering in this scenario might serve to address the tension in my body and which leads to an energetic change in my anger level. It is a high-intensity sport that matches the physical energetic expression of my anxiety that shows up as irritability.

Change in Diet

Most of our neurotransmitters are carried from gut to the brain via the Vagus Nerve (9). One of the primary neurotransmitters is Seratonin, 90% of which is stored in the gut. When information travels along the Vagus Nerve, blood sugar levels can affect how that information is delivered. Therefore, too little or too much sugar to the brain can lead to irritability, anxiety, and inattention (may be mislabeled as Bi-Polar, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)(10). So what are some things you can do to help regulate your diet, without consulting your doctor? You could: reduce consumption of foods containing preservatives and other chemicals, prepare healthy meals, eat fresh foods (fruits and vegetables), and reduce your use of sugar (10). These are just some simple solutions, however if you have Diabetes or a complex medical condition which requires consultation, please consult your physician before making any dietary decisions.

Non-physically we might see solutions looking like:

Meditation

While it might seem too easy, meditation is a simple solution to address the anger expression of anxiety, as it builds awareness of ourselves. Below is a quick video explanation of meditation, but in short, it is a practice of focusing on the present to become more aware of what is going on around us in the moment. This solution comes from a family of interventions called mindfulness-based interventions, of which multiple studies support as an intervention for anxiety and ASD presentations (see 6–8). These interventions are great for supporting emotional regulation. In my scenario, both the sudden shift in anger from a 2–7 and the ruminations which reinforce the anger are addressed with this solution. Using meditation, while it sounds counter-intuitive, forces the brain to stop. Part of the problem with anxiety in people with ASD can be the processing speed of the ruminations. Many people are not aware that a message is on repeat (e.g. “She doesn’t love me because she can’t follow through with plans”, etc.), or that it increases energy; which makes it difficult to derail the emotional expression. However, by forcing myself to meditate, I am forced to attend mentally to the present, and in turn, notice my energy level changing, and my mind on repeat. Once aware, I can then interrupt the thoughts, and challenge the negative thought on repeat. This solution matches both the expression,

non-physical, and high intensity.

Exposure-based Solutions

One of the greatest challenges I hear from people with ASD and anxiety, is fear of failure. For me, I challenge myself to be brave and face my challenging situation (e.g. talking to my significant other to tell her how I feel). There is an Exposure Cognitive Behavioral Therapy program for managing anxiety in children called “Facing Your Fears” (FYF), which is for children with ASD and anxiety. Children who participated in FYF showed a 66% positive change in anxiety related disorders, as compared to those in the treatment as usual, which only reported a 20% change in condition (9). If you have a child with ASD and Anxiety, consider pairing rewards for tasks that demonstrate bravery. For instance, if taking a shower is scary, consider rewarding your kid for taking a bath and being willing to clean him or herself. The thought being we want to reinforce brave behaviors.

In my example, when my energy has decreased, after a combination of bouldering, meditation, and dietary changes, I must have a conversation with my significant other to outline my concerns in a respectful way. Again, what must be stressed here is matching energetic expression with intensity and form of expression (e.g. low intensity, and non-physical solution).

In closing, as we have demonstrated, there is no one “right” solution to address anxiety around this pandemic known as the coronavirus. However, when it comes to you or your loved one(s) with ASD, refer back to figure 1‒1, and try to gauge how the anxiety is presenting itself today. It can be physical or non-physical, high-intensity or low-intensity, or maybe somewhere in between. No matter the scenario, I hope these suggestions help you during this time.

By Sean M Inderbitzen, APSW

Sean Inderbitzen APSW is a Behavioral Health Therapist at Northlakes Community Clinic, who lives with Autism Spectrum Disorder and provides psychotherapy to children, adolescents, and adults.

References

(1) Hofvander, B., Delorme, R., Chase, P., Nyden, A., Wentz, E., Stahlberg, O., et al. (2009). Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal- intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 9(35).

(2) Gaus, V. (2013) Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Guilford Press. 243.

(3) Russell Lang, Lynn Kern-Koegel, Kristen Ashbaugh, April Regester, Whitney Ence, WhitneySmith, et al. (2010) Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review

(5) Sizoo, B. B., & Kuiper, E. (2017). Cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness based stress reduction may be equally effective in reducing anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 64, 47–55.

(6) Kiep, M., Spek, A. A., & Hoeben, L. (2015). Mindfulness- based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: Do treatment effects last? Mindfulness, 6(3), 637–644.

(7) Conner, C. M., & White, S. W. (2018). Brief report: Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of individual mindfulness therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 290–300.

(8) Reaven, J. et al. (2011). Facing Your Fears Facilitator Manual. Brooks Publishing, 9.

(9) Johnson, Mindy (2019). Mood Regulation without Medication.

(10) Your Gut Can Influence How You Feel (2018). Retrieved from bodyecology.com/articles/your-gut-can-influence-how-you-feel-it-all-starts-with-seratonin